Whereas the Montreal Protocol in 1985 created a fund to

reimburse countries for the incremental costs of banning ozone-depleting

chemicals, later international agreements, such as the Kyoto Protocol, oriented

to reducing global warming have not given countries, including developing nations

such as China, a financial incentive to reduce carbon emissions. In fact, the

U.S. Government rejected the Kyoto Protocol because the reductions only applied

to developed countries. Even though China reduced its carbon emissions per unit of GNP by half from 1990 to

2010 by investing in alternative energy sources and mandating that polluting

companies publicly disclose their respective emissions, the amount of

emissions continued to increase dramatically through the period. How do we discern whether the Chinese government has done enough? Furthermore, are other countries enabling China and thus indirectly responsible and thus culpable too?

The steep rise in carbon emissions in China from 2003 demonstrate just how misleading incremental, or marginal, changes can be. Even China's goal of a 20% reduction in emissions by 2020 may not mean much in terms of the total amounts emitted.

Because CO2 is a “stock”

pollutant—meaning that global warming is a function of the total amount of

accumulated CO2 in the planet’s atmosphere (regardless of when added)—a

country’s total emissions figure is key (total accumulated as well as annual

amounts). As the following graph shows, China would have to do much more than

it had accomplished during the first decade of the twenty-first century.

By 2010, industrialized countries had become large net-importers of products such as steel whose manufacture involves sizable CO2 emissions.

Developed countries have enabled China’s emissions to the

extent that they are “contained” in products exported. The increase for China

from 1990 to 2010 (blue and red bars in the bar-graph below) is astonishing. So

too is the increase in carbon emissions “embodied” in products imported by

developed countries. Interestingly, the E.U. imported more product-emissions

than did the U.S. both in 1990 and 2010. The larger manufacturing output of the

U.S. may explain much of the difference in the respective nets. Europeans

critical of the U.S. for walking away from the Kyoto Protocol may be surprised

to learn that their country has been enabling foreign carbon-emissions more.

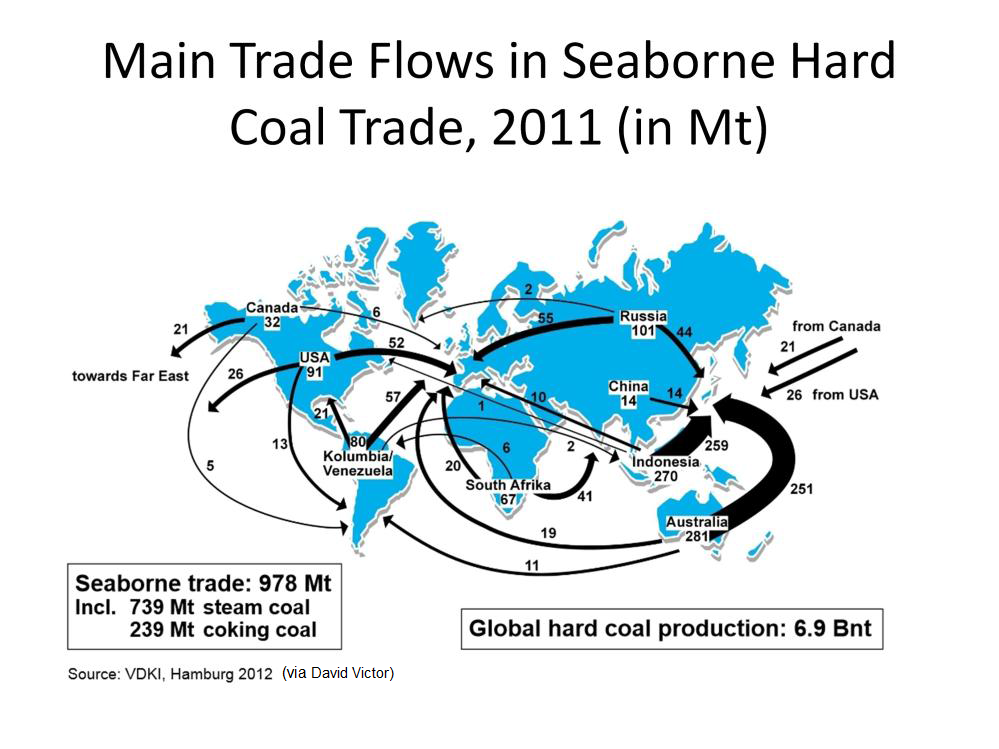

The thick black lines heading to China from Australia and Indonesia stand out in this map, suggesting just how much carbon China emitted in 2011.

Coal exports to China can be understood as another instance of enabling. As

global shipping costs for bulk commodities such as coal dropped significantly, the

amount of the commodity traded increased significantly. Obviously, major

exporters have a financial incentive to oppose global carbon-emissions limits

being written into multilateral treaties. In 2011, Australian companies extracted

a lot of coal, a majority of which went to China. Indeed, the sheer magnitude

of coal imported into China can tell us a lot about just how much carbon China

continued to emit in spite of the government’s forays into alternative energy

sources. Even though parts of Australia had been burned by the hole in the

ozone layer decades before 2011, the continent’s government and mining

companies have had a financial incentive to keep China from shifting to wind

and solar energy sources sufficiently even to level-off China’s annual carbon

emissions.

Had the Kyoto Protocol included carbon limits for developing countries, complete with “self-enforcing”

financial incentives (e.g., an international fund to cover incremental costs of

compliance) and disincentives (e.g., other countries in the treaty can boycott trade

with non-compliers), in spite of opposition from major coal-exporters, perhaps

China would have curtailed the upward trend in the country’s total

carbon-emissions even by 2010. Lest it

be thought that the dictatorship in China has far outpaced the world’s largest

democracy (i.e., India) as a “global citizen” enabling our species to have a

future, keeping global warming to within 2 degrees (C) will require much more

from China, and indeed the world.